Aristocracy of Talent: Social Mobility Is the Silver Lining to America’s Inequality Crisis

The Daily Beast

Yes, wealth concentration is insane. But the ways in which wealth is shifting are surprising—and give reason for a little optimism.

In an age of oligarchy, one should try to know one’s overlords—how they made their money, and where they want to take the country. By looking at the progress of the super-rich — in contrast with most of us — one can see the emerging and changing dynamics of American wealth.

To get a sense of these trends, researcher Alicia Kurimska and I tapped varying analyses from the Forbes 400 list of richest Americans. No list, of course, captures all the relevant data, but the Forbes list (I am a regular contributor to that magazine’s website) allows us to look not only at who has money now, but how the dynamics of wealth have changed over the past decade or more.

The bad news here is that our oligarchs are getting richer, and, unlike in the decades following World War II, they are primarily not taking us on the ride. Indeed at a time when middle-class earnings have stagnated for at least a decade and a half, the oligarch class is making out like bandits. This, of course, extends to much of the infamous “top 1 percent.” The share of income of the top 1 percent of households in the US increased from 10 percent in 1979 to upwards of 20 percent in 2010, as famously found by economist Thomas Piketty and Emmanuel Saez.

But if the highly affluent are thriving, the super-rich are enjoying one of the brightest epochs since the days of the robber barons. These people , according to a study by economists Steven N. Kaplan and Joshua D. Rauh, the top 0.0001 percent of 311.5 million US individuals. In constant 2011 dollars, their wealth has grown seven-fold since 1992 — from $214 billion in 1982 to $1.525 trillion in 2011. This at a time when most Americans have endured little or no real income growth.

What we are talking about is a concentration of wealth and power unprecedented since the turn of the last century. According to an analysis by the left-leaning Institute for Policy studies, America’s 20 wealthiest people own more wealth than the entire bottom half of the population—152 million people in 57 million households. The top 100 own as much wealth as the entire 44.5 million-strong African-American population (there are only two African Americans on the list), and the top 200 have more than the entire 55 million-strong Latino population (there are 15 Latinos on the list). To make an international comparison, the 400 have more wealth than the GDP of India, arguably the most up and coming big economy on the planet.

The Rise of the self-made

Not all the news is bad, however. The proportion of the 400 who inherited their money has been steadily decreasing. There are more self-made billionaires than existed in the 1980s. Kaplan and Rauh report that since the 1980s the share who grew up wealthy fell from 60 percent to 32 percent.

This does not mean so much the return of Horatio Alger — the share who grew up poor remained constant at 20 percent — but that most super-wealthy came from affluent but not rich families, which gave them some head start, notably in education.They did not hand the keys to the kingdom to their offspring. Rather than country clubbers clipping coupons, the rich since the 1980s have become largely, if not entirely, self-made.

But origins are not the only thing that has changed in this era of oligarchy. So too have the industries that create the wealth — largely represented by the shift toward technology and finance — and, not surprisingly, where that wealth tends to concentrate. These shifts are already changing not only our economy, but also the outlines of political power, as industries friendlier to Democrats, notably tech and finance, supplant those, notably energy, that have long been associated, particulary in the last decade, with the Republicans.

The shift in the fortunes of the super-rich reflect changes in our industrial structure over the past third of a century. The big winners have been in scalable businesses where capital is king and rapid accumulation possible. Rauh and Kaplan, for example, report that the big winners have emerged not only in tech, but also include owners of retail and restaurant chains, tech firms and private finance, including hedge funds Over the period between 1982 and 2012, finance’s share grew the most, followed by technology and mass-retailing.

Who’s losing ground? The big losers are a bit counter-intuitive. Despite all the attacks on “big oil,” energy has actually suffered the biggest decline in terms of presence on the Forbes list. Energy, for example, used to account for about 21 percent of the 400, but that has shrunk to about 11 percent. Equally puzzling, amidst a high-end building boom (not so much for the hoi polloi), real estate’s share has dropped about as much. Perhaps less surprising are the losses among non-tech based consumer industrial companies.

Since 2012, the year the Rauh study was completed, the tech billionaires have, if anything, expanded their presence, while it’s likely that, with the drop in energy prices, the oil barons will slip even further. On the 2014 list, for example, in terms of dollar gains, five of the top six were from the tech sector, led by Mark Zuckerberg, whose fortunes increased by a remarkable $15 billion (Warren Buffett was the lone exception). Mark Zuckerberg’s gains were larger than the $12 billion increase between Charles and David Koch, even at the peak of the energy boom.

Fully half of the top 10 on the list came from the tech community, with the balance made up of Wall Street/finance people (Buffett and Michael Bloomberg) along with the Kochs and David Walton, the youngest son of Wal-Mart founder Sam Walton.

The New Geography of Wealth

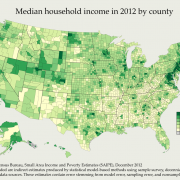

Perhaps more surprising has been the shift in the location of the rich. Despite the rise of the tech oligarchs, the biggest gainers over the past decade have not occurred in California but in New York, Florida and Texas. This reflects not only the power of Wall Street and the investment class (some of whom have decamped to Florida), but the growing diversification of the Texas economy.

Oil, of course, still plays a critical role among the Texas rich, but it’s much more than that now. The richest people in the Lone Star State include Alice Walton, the Ft. Worth-based heir to the retail fortune, but also Austin tech mogul Michael Dell, Dallas financier Andy Beal, and San Antonio supermarket mogul Charles Butt. The first energy billionaire, pipeline entrepreneur Richard Kinder, clocks in as fifth richest Texan. Even if energy remains weak for the next decade, Texas seems likely to keep producing gushers of billionaires.

If we break the rich list by region, it’s no surprise that New York, long the nation’s premier financial center, would rank first, with 82 billionaires. In second place is the San Francisco area, with 54 billionaires, most of them tied to technology. The Bay Area, with about one-third of the population, surpasses third-place Los Angeles, with 34. Miami ranks fourth with 27, Dallas fifth with 19; each is ahead of the traditional second business capital, Chicago, which ranks sixth with 15, just a few paces ahead of Houston with 12.

The Future of Oligarchy

What is the future trajectory of wealth in America? One thing seems certain: the twin tech capitals of Bay Area and Seattle, now home to nine of the 400, are likely to expand their reach. One clear piece of evidence is age; people generally do not get richer when they retire. In contrast, virtually all self-made billionaires under 40 are techies.

Of course, the biggest growth can be expected in the Bay Area, particularly as tech people think of new ways to “disrupt” our lives – for our own good, of course. Whole industries such as music, movies, taxis, real estate are increasingly controlled from the Valley; as these companies wax, many of the old fortunes made in these fields will begin to wane. This is also true across the board in retail, where Seattle’s Jeff Bezos now looms as a colossus greater than any individual chain of traditional stores.

Ultimately what will make “the sovereigns of cyberspace,” to quote author Rebecca MacKinnon, so dominant is precisely what made John D. Rockefeller so rich: control of markets. Google, for example, accounts for over 60 per cent of Internet searches. It and Apple control almost 90 percent of the operating systems for smartphones. Similarly, over half of American and Canadian computer users use Facebook, making it easily the world’s dominant social-media site.

And soon, they, like the old Wall Street elites or the energy barons, may be able to regard the government as yet another subsidiary. They will benefit greatly from the likely electoral victory of the Democrats, who are increasingly dependent on tech contributions, while the old economy oligarchs already in retreat, in energy, manufacturing and real estate, fade before them.

The prognosis for the future of American wealth, then, is for an ever-expanding role for both tech and private investors, and a gradual shift away from basic industries that are geared to our diminishing middle class. This may not be good for America but will be wondrous indeed for the ever more powerful, and outrageously wealthy, new ruling class.

This piece originally appeared at The Daily Beast.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com. He is the Roger Hobbs Distinguished Fellow in Urban Studies at Chapman University and executive director of the Houston-based Center for Opportunity Urbanism. His newest book, The Human City: Urbanism for the rest of us, will be published in April by Agate. He is also author of The New Class Conflict, The City: A Global History, and The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. He lives in Orange County, CA.